What the polar explorers teach us about resilience

There is no cure for paralysis and I am paralysed. So my motivation to connect people around the world to create a cure may simply seem like a personal desire to walk, to feel, to be my old self again. The fall that broke my back in 2010 leaving me with no movement or feeling below my waist certainly pointed my compass towards this frontier that I now explore, but that alone could never sustain what this expedition requires.

By day, I am a lab rat. I am shaved and willingly, joyfully caged in my robotic legs. I am wired to technology that unfolds the map of the inside of my body like the uncharted cosmos and with scientists, amateurs and other pioneers we explore it. By night, I connect. I try to bring foundations, investors, scientists, engineers and paralysed patient advocates together to be part of the solution. I can do all this because I believe that my real motivation, (the intrinsic motivation that comes from deeper within me than the extrinsic reward of walking, feeling, being my old self again), is to find what lies beyond this unconquered frontier of paralysis, to find what is on the other side of the hill.

And it is vital that we understand what really motivates us and why. Otherwise we could never sustain the effort. The scientific research programme we have created in which I am a subject is producing incredibly useful data, but it may well lead to a breakthrough that benefits my fellow paralysed. So something more than the inarguable self-interest keeps me in the lab, keeps me working.

The heroic age of polar exploration has long been a font of insight for me. And even more so now as I figure out how these explorers faced their frontiers. So, I travelled as close as I could to a man who is to me one of the most fascinating of those explorers, a man called Tom Crean.

He was a titan.

Born in Annascaul, County Kerry in my home country, Ireland, he returned and opened a pub there in 1916 after his polar exploration ended. Simply called, The South Pole Inn, it is still open and is a memorial to his incredible life.

Simone, my fiancée, and I toasted Tom with a beer named after him. Simone described the 18/35 logo on the pint glass, but I couldn’t recall the significance of those numbers even though I had listened to the audiobooks of almost all the stories of polar exploration before my own Antarctic adventure back in 2009. Having lost my sight when I was 22 I turned from international rower to a blind adventure athlete and I competed in the first South Pole Race since Scott and Amundson had competed for the prize of being the true first to the pole over a hundred years before. It was how I had marked my 10-year anniversary of going blind.

Surrounding us on the walls of the pub were articles detailing Antarctic exploration. Crean was on teams led by both Sir Ernest Shackleton and Captain Robert Falcon Scott. As Michael Smith, author of “An Unsung Hero”, points out, Crean spent more time on the ice than either of those two Polar heroes; he was pivotal to three of the four major British expeditions to Antarctica.

Source: The Mark Pollock Trust

Initially he served under Scott on the Discovery from 1901 to 1904, then on his fatal Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole from 1910 to 1913 and finally on Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition on Endurance from 1914 to 1916.

It was during Scott’s ill-fated Terra Nova expedition that Tom Crean made the numbers 18 and 35 his own. At only 168 statute miles (270 km) from the Pole, Scott ordered Tom Crean, William Lashly and Lieutenant Edward Evans to return to base. Scott recorded the sorrowful moment in his diary: “Poor old Crean wept”.

Scott went on to reach the South Pole only to find Norwegian Roald Amundsen’s flag planted there first. Scott and his team then perished on the return journey.

Crean, Lashly and Evans made it off the polar plateau one month after leaving Scott and the others, but Evans began to display the debilitating symptoms of scurvy. In the harness for up to 13 hours a day, Crean developed snowblindness and hauled the sledge, his eyes bandaged with a tealeaf poultice. Risking crevasses, broken bones and certain death, the three lashed themselves to the sledge and slid 2,000ft onto the Beardmore Glacier to save three precious days of marching and food. But then Evans collapsed and with two weeks of travel out from the safety of Hut Point, Crean and Lashly began hauling Evans on the sledge.

On 18 February 1912, they arrived at Corner Camp with food supplies running low. With one or two days’ worth of rations left, they still had four or five days to travel. So, facing death, Crean volunteered to go for help. He had no sleeping bag or tent and was already physically exhausted.

Lashly held open the round tent door flap to allow Evans to see Crean depart. Evans remembered: “He strode out nobly and finely – I wondered if I should ever see him again.” Yet, with only two sticks of chocolate and three biscuits (keeping one in his pocket in case of emergency) Crean completed the 35 statute miles (56 kms) in a punishing 18 hours. The rescue was successful and Lashly and Evans were both brought to base camp alive. Crean more than earned his Albert Medal, then the highest award for gallantry.

Crean’s own survival, the rescue of his companions and his desire to return to Antarctica, despite this experience, still intrigues me. I can understand the motivation for Amundsen, Shackleton and Scott – the adventure, the recognition, the money and the influence. My own 43 days in Antarctica racing to the South Pole was fueled by my desire to compete, to do something bigger than me, bigger than my blindness, maybe to take a small place in polar history.

Everyone else, including me, seemed to have an obvious reason to be there. But why did Tom Crean keep going back? He was not an officer or a leader on any of the expeditions; he gained very little public recognition or wealth. So, what drove him to go? What allowed him to survive?

I asked Crean’s biographer, Michael Smith. He said: “Crean was the type of man who wanted to see what was over the other side of the hill”. So, maybe curiosity and adventure were the drive. It also may have been that the other side of the hill was a great deal better than life in rural Ireland in the late 19th Century; maybe joining the British Navy was just a job? But this was a job that required him to endure torturous conditions, to put his life on the line.

The compelling but probably apocryphal story goes that the men who joined Shackleton did so in response to his newspaper ad for the Endurance expedition: “Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in event of success.”

It is unlikely that Shackleton would have created an advertisement with any pessimism in it, but I am interested in the type of people who would have joined any exploratory Polar expedition, because I think motivation is rarely about the extrinsic factors, it’s rarely about money, recognition or status. They are all so easily granted and so easily taken away. People like Crean have a drive that comes from somewhere else, somewhere deep within, something intrinsic.

Norwegian explorer, Fridtjof Nansen, whose name and face were on my skis that took me to the South Pole, wrote about this very notion.

“It is within us all, it is our mysterious longing to accomplish something, to fill life with something more than a daily journey from home to the office and from the office, home again. It is our ever present longing to surmount difficulties and dangers, to see that which is hidden, to seek the places lying away from the beaten track; it is the call of the unknown, the longing for the land beyond, the divine power deeply rooted within the soul of man; it is this spirit which drove the first hunters to new places and the incentive for perhaps our greatest deeds – the force of human thought which spreads its wings and flies where freedom knows no bounds.”

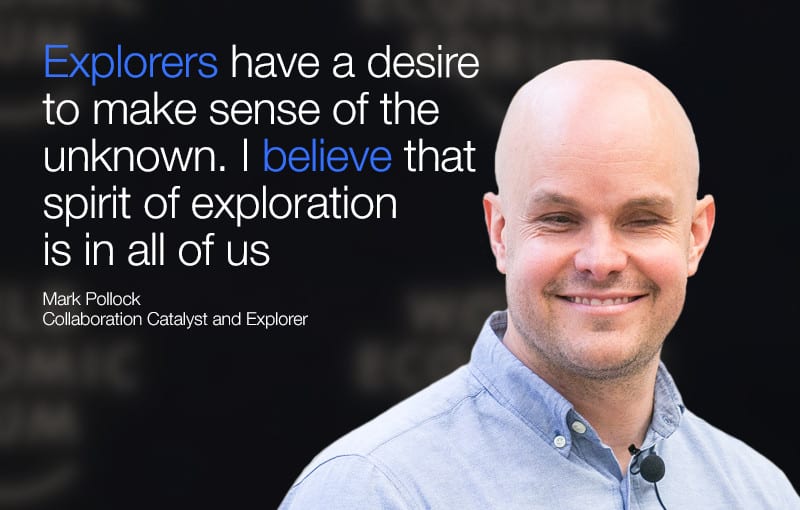

Explorers have a desire to make sense of the unknown. I believe that that spirit of exploration is held deep within us all.

Perhaps Nansen articulates what we must try to find as we explore our own frontiers when he says: “It is within us all.” Whatever the challenge, the motivation to keep going must come from somewhere deep inside us. External motivators are always temporary.

The answer to the question of why we do what we do is an internal one, often held privately, but one that if answered honestly will be the one that gets us there. I know that Crean must have had an answer to that question when he walked those 18 hours to cross those 35 miles of ice, uncertain if help would be waiting at the end. If he didn’t, he would never have made it.

As originally appeared on markpollock.com.

Recent Posts

- Top 5 Keynote Speakers for UK Events in 2025

- Front Row Speaker Caroline Currid Begins New Role with Munster

- Front Row Speaker Amy Morin’s 13 Exercises to Mentally Strengthen your Children

- Front Row Speakers’ David Meerman Scott on How You Can Turn Customers into Fans

- Front Row Speaker Eric Partaker on Why Your Lack of Respect is Hurting You